Catch Shares Are Catching On

Economic logic applied to commercial fishmerman to motivate them to abandon eco-lunacy

Fish first appeared in our oceans around 525 million years ago. In 1950 their descendent species remained plentiful. But just 50 years later populations of the larger ones we love to eat had plunged by 90%. In an evolutionary blink of an eye, we hungry humans had gotten so good at foraging for fish that we had overrun their pace of self-replication.

As populations declined we waded increasingly deep into piscatory propagation. At the eco-lunatic extreme, we’ve emulated land-based CAFOs (concentrated animal feeding operations) creating aquatic equivalents that have produced similar unintended eco-damaging consequences. At the eco-logical extreme we’ve learned how to create complex coastal ecosystems optimized to produce the fish we love to eat. An example is Veta La Palma, briefly profiled in a clickable “learn more” at the bottom of our home page.

We’re also taking another eco-logical approach: becoming game wardens. If it works we will greatly increase seafood quantities we can sustainably harvest, restore abundance to vast undersea ecosystems edging continents and islands, and revitalize economies of coastal towns, while letting Mom Nature do most of the heavy lifting.

This post is about a key component of an emerging wild fish management system.

How NOT to Manage Wild Fish

Initially, fishery managers emulated the tactics of wardens managing hunted land-dwelling game like deer and moose. Three of the components worked pretty well.

Minimum fish size limits

Fish needed to exceed a specified length to be kept. Those that didn’t had to be thrown back.

Yearly catch maximums

Fish in waters under a fishery manager’s jurisdiction were counted, this data was used to assess a fish species’ ability to maintain or increase its population, and to generate a catch maximum that has come to be called Total Allowable Catch (TAC).

Fishing category quotas

Quotas were set for commercial and recreational fishing categories. Quotas factor in TAC as well as assessments of how well fishermen* have met quotas in previous years. Percentages of total quota were allocated to an area’s commercial and recreational fishing fleets.

*We couldn’t find a suitable de-gendered word to refer to people who fish. Fishers, fisherpeople, fisherfolk and piscators just weren’t floating our boat.

These other two…not so much. They had unintended consequences.

Fishing seasons

Beginning and ending dates of an annual fishing season for each protected fish species were designated. Fish caught out of season had to be thrown back.

Fishing seasons motivated fishermen to catch as many fish as possible in-season without regard to impact on fish stocks, resulting in aggregate quotas being exceeded. They perpetuated what economists call a tragedy of the commons, where the incentives of individual users guided by their self-interests deplete the resource through their collective actions.

Catch-and-keep maximums

Limits were set for per-trip fish brought in to port. Per-trip limits for commercial fisherman were typically set by aggregate weight, and for recreational fishermen by number of fish.

A vicious cycle ensued: aggregate catch maximums were exceeded, so fishing seasons where shortened, often down to just a few days, and per-trip catch limits reduced. Commercial fishermen came to despise regulators and despair that fishing would ever again provide them a decent living.

These two rules also caused other dire unintended consequences: more fish died, fisherman were compelled to fish in conditions that risked their lives, fishing costs rose, and fishermen’s financial returns fell. Here are some of the reasons why:

Danger level

Fair weather or foul, fisherman were compelled to maximize their in-season catch, leading to fishing while sleep deprived and during rough weather.

Catch forecasting

Fishermen couldn’t predict how many fish they will catch, so they couldn’t make commitments to customers.

Overhead

Per-trip per-boat catch-and-keep limits not only caused extra boat trips resulting in more fuel use, but also motivated fisherman to buy more boats to bring in more catch, adding labor and equipment costs.

Black markets

Compliance measures were lax and fisherman/regulator relations broken, so black markets developed, causing more fish to be killed.

Labor

Fishermen needed deckhands at the same in-season times, causing a demand spike for part-time workers. Qualified deckhands were hard to find: One fisherman noted that he preferred heroin addicts to crackheads.

Price

Fish freshness is important to customers, especially for fish favored by gourmet chefs and home cooks. However, fishing seasons caused all to be caught in the same short periods of time so gluts ensued, resulting in lower prices fetched by fishermen.

Bycatch quantity

Fish inadvertently caught out of season weren’t allowed to be kept: millions of pounds of bycatch were caught each year. Also in-season per-trip quotas encouraged fishermen to fish closer to port where a greater proportion of fish they caught were too small to keep, increasing bycatch.

Bycatch mortality

Bycatch died when not thrown back soon enough. Some species died if they were brought to the surface too quickly. All were more likely to die if fishermen were neither incentivized to prioritize bycatch survival nor monitored in relation to bycatch handling.

A Better Approach Emerged and Spread

In the late 1970s, first in the Netherlands, then in Iceland, Canada and New Zealand, fishery managers began having success with an approach that aligned fishermen’s incentives with the restoration of over-fished seafood stocks and began to remedy the tragedy of the commons. Guided by the best science about protecting fish and their habitats and by their own fishing experience, they worked to create a virtuous cycle where each year would provide more fish to catch until abundance was maximized. Under the catch share system, fishermen became eco-logical fish population nurturers, working with nature to help it provide more and more food for us.

What, you ask, were the innovations that led to these alternative outcomes? They were to abolish fishing seasons and per trip catch limits and replace them with:

Individual percent catch shares

Designate a finite list of fishermen with exclusive rights to fish for the protected species. Allot each of them a long term percentage share of annual fishing quota, thereby providing an incentive to increase fish populations.

Extensive data collection

Capture more complete and accurate data that, along with strict and enforced rules, assures fisherman compliance with annual catch quotas and prevents black markets from forming.

Also use data to both increase fishing efficiently and help fish stocks recover more quickly.

Because fisherman owned a percentage of the catch, and because stringent compliance measures made cheating both hard to do and not worth the risk of being caught, fishermen’s interests were aligned with common interest: the more abundant the commons became, the more fish fishermen were able to catch. All boats rose.

The approach has caught on and is working well in American waters, especially in areas with a large proportion of commercial fisherman to recreational anglers. According to the Environmental Defense Fund, catch share systems have allowed more than two-thirds of the seafood supply in the U. S. to become sustainable, with over 100 species on a path to recovery.

This approach also addresses the unintended consequences of fishing seasons and daily quotas listed above. In addition it leads to active participation by fishermen in reducing bycatch, reducing the mortality rate of bycatch, and fishing more efficiently. For example, here are some of the things Gulf of Mexico red snapper fishermen agreed to do:

no-fish zones

Establish marine protected spawning areas off-limits to fishing

catch trading

Trade catch to reduce bycatch. When fishermen unintentionally catch over-quota fish they can lease quota from fishermen who are under quota

hook size

Use undersized hooks to avoid catching mature fecund females that are critical to snapper population replenishment

Fish tagging

Tag individual fish with catch location and fishermen data, and brand fish so tagged “Gulf Wild” to give assurance that these fish are cleanly caught and are actually red snapper (as species mislabelling is rife)

catch speed

Bring fish up to the surface slowly enough to reduce snapper mortality rate from over 67% down to around 12% by reducing the incidence of air bladder rupture

impact mitigation

Use information about locations where other fisherman had fishing success NOT to find a place to fish, but rather a place to avoid to even out fishing impact across an area

Why Restoring Seafood Abundance Is So Important

Larger fish populations that allow us to catch more fish as they continue to become more plentiful is of course great for us, whether we depend on fish for our livelihoods, sustenance or dining pleasure. But there are also important aquatic and terrestrial benefits.

It’s good for oceans

Fish excretions provide more nutrients to seagrass and algae than any other source. They boost seagrass and algae growth rates and expand the amount of area these bottom-of-the-food-web plants occupy. This increased marine biomass in turn provides more food for ocean creatures higher in the food web that ultimately make it into the bellies of the big fish we eat.

Research on the absence and reintroduction of key top-of-the-food-web species on ecosystems suggests that restoring them would have a positive impact on the size of and biodiversity in their ecosystems.

It’s good for land

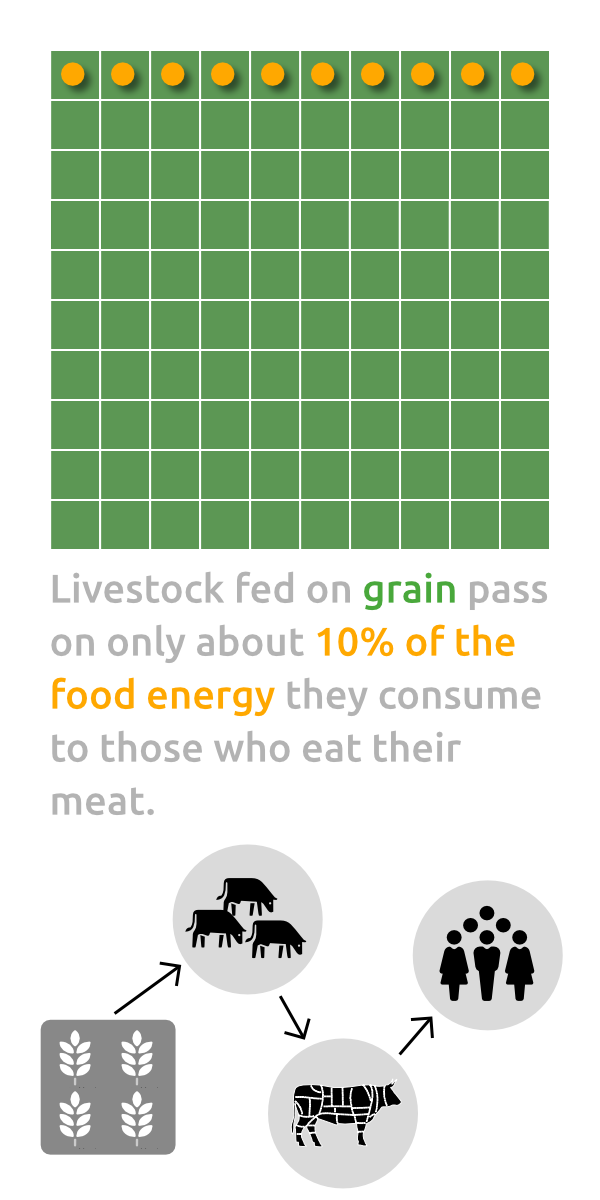

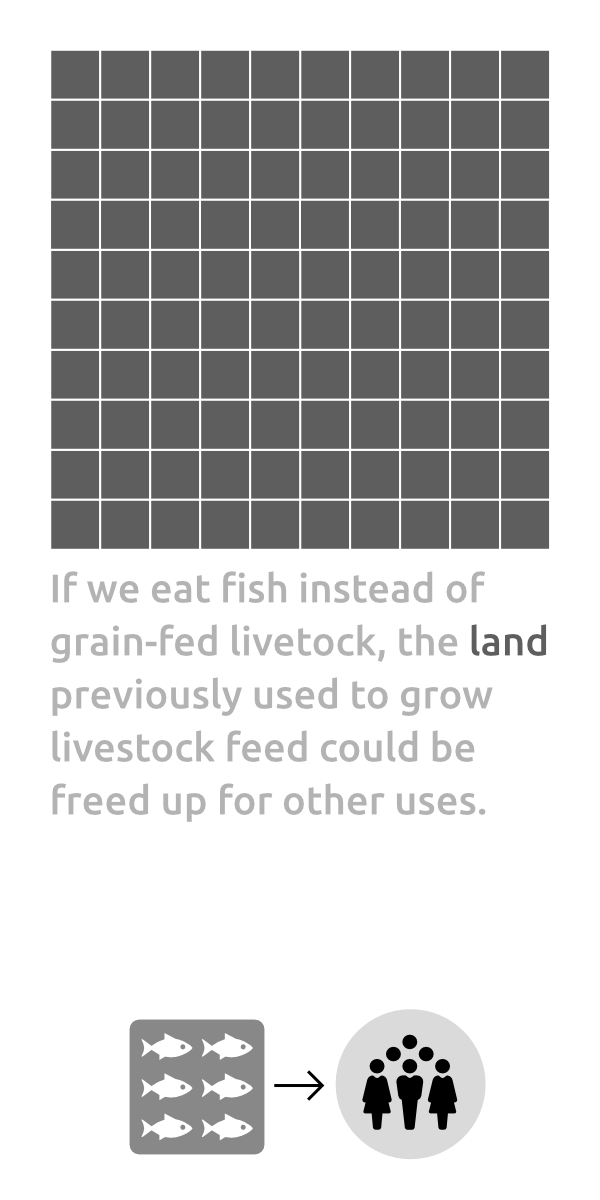

There are many competing uses for land suitable for growing crops now fed to livestock. If we can increase the percent of fish and decrease the percent of grain fed livestock meat we eat, we can free up arable land for more efficient food-producing use, as the diagrams below show:

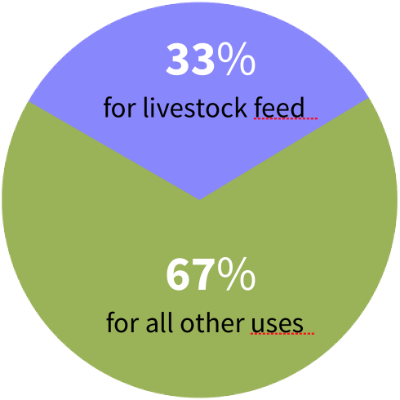

Livestock fed grain compete with us for food. Wild fish don’t: they largely eats plants and sea creatures we aren’t interested in eating. As one-third of all cropland land worldwide is devoted to growing feed for livestock, there’s plenty of it to convert to growing food for us, providing ecosystem services, and maintaining biodiversity.

Global cropland used to grow livestock feed (2012)

Three Reasons for Optimism

1 Clear jurisdictions for action

Fish stock restoration can be accomplished without requiring hard-to-achieve international agreements. Most fishing for over-fished species gets done within 200 miles of shore in waters that are under the uncontested jurisdiction of single countries who can set and enforce their own seafood restoration policies in their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs)

2 Relatively biodiverse and intact undersea ecosystems

Ecologists focusing on assessing ocean ecosystem health, while deeply concerned about the increasing damage we are doing — especially through increasing ocean acidity and temperature — are nevertheless encouraged because sea bed ecosystems are much more intact than those on land, making restoration more possible. In support of this assertion they point to 514 documented extinctions of land dwelling animals since the year 1500, versus just 15 documented ocean animal extinctions.

3 Recent successes

Finally, they are encouraged by the speed at which fish stocks protected by effective science-based fishery management are now rebounding.

Why We Chose this Topic to Be Included in our Initial Set of Posts

You may be asking yourself why a site focused on farming would, right off the bat, tackle fishery management. Here’s why:

- Fishery management has brought fishing for “wild” fish within Mimiculture’s farming bailiwick. We are no no longer simply foraging for fish: taking what nature has created on its own. We’ve begun to use our knowledge of nature to increase fish production for use by us, then harvesting the results.

- The catch share system is an important eco-logical farming model that can be used elsewhere. It takes action that helps nature restore itself, thereby increasing yields of items of value to people. A portion of resulting growing revenues can not only be tapped to manage the system, but to fund broader, deeper restoration efforts.

- Eco-tragedies of the commons are not limited to overfishing. Our planet is our ultimate commons, and many of our environmentally unsustainable behaviors involve incentives unaligned with planetary health. The catch share solution may serve as a model to address some of them.

- Coastal undersea ecosystem restoration is a huge opportunity to increase human food production. Globally we have almost 10 times the area in ocean Exclusive Economic Zones than we do in arable land. Habitat volume is further increased because coastal ocean habitat areas are much deeper than land-based farming habitats.

- It is a large and rare opportunity to simultaneously increase our food supply, restore undersea habitat, and put some proportion of arable land to better use than growing livestock feed.

- Finally, we find catch shares to be such an elegant, minimalist solution (shift incentives by granting ownership), such a civilizing one (cooperate in informed stewardship) and such a surprising one, turning what looked to be an unavoidable loss for man, fish species and the environment into a win for all.

Some Catch Share Nitty-gritty

The success of catch share systems in stimulating fish population growth is not only dependent on the ecosystem’s ability to recover and on successfully keeping fishing fleets catches at or under quota. It also depends on aspects of system design and implementation such as:

Fish habitat knowledge

Scientists are just learning the basics of how undersea ecosystems work. For example it was as recently as 2012 that they found fish excretions to be the primary source of nutrition for sea grass and algae, whereas we have known for centuries about a parallel terrestrial symbiotic relationship between large herbivores and the grasses on which they graze. If we knew more about undersea ecosystems we could do more to restore fish stocks than to decrease fishing pressures and avoid the use of fishing methods that obviously damage undersea habitats.

Fish population assessment

Scientists face a difficult task in counting fish because they are hard to spot and constantly in motion. They also face difficult decisions in allocating scarce resources to the counting process. On one hand they want to take advantage of emerging knowledge and technologies, but on the other need to record data that is consistent with and comparable to legacy data.

Managing open access fishing groups

Methods need to be found to regulate open-participation fishing groups like private anglers. Because their number cannot be fixed individual percent-based catch shares can’t be issued. As a result the old regulatory methods are being used, with predictably poor results for both fish stocks and fishermen.

In the Gulf of Mexico this issue is causing litigation among commercial fishermen, who are successfully limiting their catch to meet quotas, private recreational fishermen who aren’t, and regulators who are legally bound to protect fish populations but are subject to political pressure from recreational fishermen.

The need to reduce anglers’ catch of large “trophy” fish of some species (including red snapper) is particularly acute. Older larger fish are often disproportionately critical to a fish species spawning potential.

Working in low governance areas

Over-fished Belizean barrier reef

Local Belizean fishing boat

Developing countries with coastal populations dependent on fish they catch for basic nutrition, with less established legal systems and economies, are not able to take advantage of regulatory systems used in more developed economies. Alternate systems are just beginning to be tried. Belize has been an early success story, and other developing countries have been looking to it for guidance.

Starting in 2011 Belize developed territorial rights for fishing towns, with local committees to grant fishing rights, provide oversight, and collaborate with the national government to enforce regulations and monitor compliance. Success in the two initial test areas led to planned expansion in 2014-16 to 44% of its waters with a goal of 100% by 2020.

Premature victory declaration

As fish populations begin to recover in number they are skewed toward younger, smaller fish with less spawning potential that are nevertheless big enough to be caught and eaten. For example, red snapper in the Gulf of Mexico become big enough to catch and keep when 2-3 years old, but female snapper take 10 years to attain mature spawning potential and retain it for another 25 to 30 years. The discrepancy between perceived abundance and actual sustainable abundance can lead to pressure to increase quotas prematurely.

Ownership group legitimacy

Granting long term exclusive fishing rights to a fixed set of incumbent fishermen transfers considerable financial value to them from the public domain. It is therefore important that, in the eyes of parties with standing to protest the transfer, those who receive and don’t receive fishing rights, and the per cent allocated to each who do, are deemed to be fair.

Ownership transfer

Rules about catch share ownership transfers need to be clear, promote efficient use of resources, and avoid issues like ownership drifting into the hands of people who do not do the fishing or to corporations from outside the community.

Community impact

The mixed impacts on a fishing community caused by switching to a catch share system need to be well managed. Those who are granted shares do better in the long term, as do people who want full-time crewing jobs. However, reduction in fishing over-capacity can have negative impacts in the short term on fishermen and their suppliers and in the long term on those looking for part-time crewing work.